Understanding the Complexity of Decision-Making – Part 1

One of the Keys to Unlocking the Future Organisation?

Image: Arek Socha via pixabay.com

18-minute read

In the last three editions of our newsletter, we discussed the important role that the job description has played as one of the building blocks of traditional hierarchical organisations. We also indicated that how and where decisions are made is an important part of the way that organisations operate. During the discussions we highlighted the importance of introducing distributed authority and decision-making in future-oriented organisations, one of the Principles of Futocracy. This was predicated on the current predominant approach, which is based on some form of position or expert hierarchy in most cases, being unable to meet the challenging demands of timeliness and flexibility.

This newsletter is the first of two that explores what decision-making is and how it can be applied to assist in achieving improved decisions, more flexibility, and create an attractive environment to attract the people organisations need.

The last decade has confirmed that the bureaucratic pyramid style organisation that flourished during the industrial age has difficulty in achieving the flexibility, speed and what my colleague Dr Ross Wirth and I call the B2Me demands of individualisation of products and services in both the business to consumer (B2C) and business to business (B2B) environments. Defenders of the bureaucratic approach with its strictly enforced processes and hierarchal management systems rightly argue that it is not necessarily the bureaucratic approach that is wrong, more that it is not used effectively and, importantly, it is probably not set up as a requisite organisation as defined by Elliott Jaques (Jaques E, 1998)[i]. The work of Dr Elliott Jaques is probably the most scientific piece of work ever undertaken to make sense of organisations. Whilst this newsletter is not focused on his work it is important to spend a little time to understand his messages and how they can help us in making sense of the structure and management of organisations for the future.

Elliott Jaques, was born in Canada in 1917 and died in 2003. He studied medicine and psychoanalysis. He analysed tens of thousands of positions in a wide diversity of organisations and empirically established a strong correlation between mental processing ability (cognitive capacity), time horizon of work, and complexity. He was a pioneer in Stratified Systems Theory and author of the seminal book Requisite Organisation.

He maintained that whilst people considered a 4D world of human life as three spatial and one time-based, there are in fact three spatial and two-time dimensions. In the ‘normal’ world view we have Chronos, which is the time measured by the clock. However, there is also Kairos. Kairos is informed by the memory of the past, perception of the present, and intention of the future.

Jaques saw Cognitive ability as being that quality of mind that defines the outer limit of the horizon of intention. This means that it is not some vague notion about a vision of the future. It is the mental processing to capture the future and understand the complexity associated with bringing it into being and having the ability to exercise judgement and discretion in overcoming obstacles on the way to that horizon. His research identified different levels of work require different modes of thinking just as water is different to steam, which is different to ice.

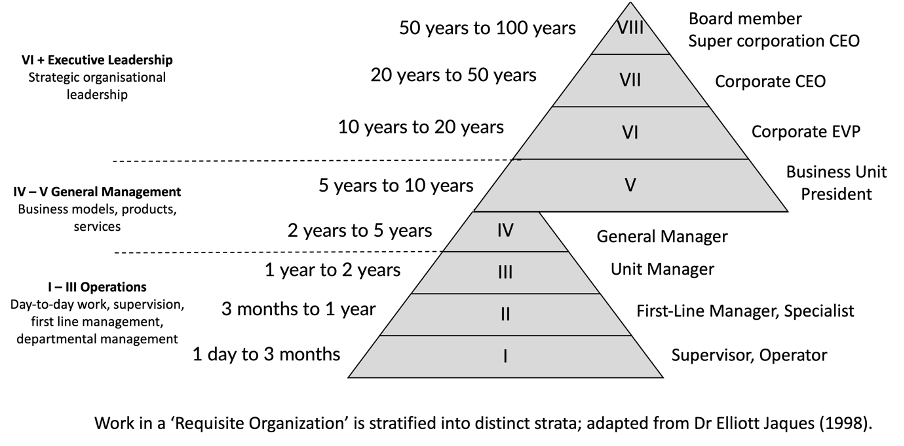

He broke down the work into eight levels (figure 1), which he called Modes and against each mode defined their associated time horizons. He reserved a ninth (and above) Mode for those who could go beyond the realm of organisations such as Christ, Buddha, Confucius, Mozart, Galileo, Einstein, Gandhi, Winston Churchill, and a few business leaders like Konosuke Matsushita and Alfred Sloan who graduate from running Mode VIII companies to looking out for society's development.

Figure 1: The Modes of a Requisite Organisation

When making sense of the problems of current traditional hierarchical organisational designs, Jaques’ work is helpful because it is based on the understanding that no organisation can ascend beyond the level of work practised by the most senior person in the organisation. This means that if that person cannot operate at the level required by that role, it will cause compression of the roles below it. The effect is that the competent people become frustrated that they cannot be effective in exercising their discretion and judgement that is suited to their capability. At the same time, a managerial leader occupying a role that is too big for them will feel stressed and ineffective.

The extensive work of Jaques also tells us is that there is a tight fit between accountability for getting the job done and authority over the resources needed to do so.

What that means will be discussed further when examining the way that decisions are made and the boundary conditions that need to pertain in non-traditional organisations that break away from the bureaucracy and formality associated with traditional organisations.

We contend that to achieve this in organisations based on the Futocracy approach to work means we must have the right people in the right place (roles) with the appropriate cognitive ability to do the right work. Future organisations must also consider more the natural social mammalian process of hierarchy, which in this context is the psychological process of ranking when socialising through work. This brings us back to last week’s newsletter and the importance of those in roles being able to co-design their roles with the colleagues they interact with daily, which is seldom the case today.

There have been many attempts to re-design organisations to be more flexible and timelier in their response to external demands for change or bespoke services. Regular readers of our newsletter will know that Ross and I have been researching these ‘alternative’ approaches to organisational design as part of our quest to identify a ‘future-proof’ approach to business where change is just part of the daily business.

Whilst exploring the shape and functionality of organisations, we found that the decision-making process is one of the important keys to the way the organisation is designed. We argue that what type of decisions are made, where and by whom, sets the scene for the processes, rules, and procedures of the organisation. The difficult question for us was, which of these comes first, and to what extent is the organisational structure a victim or driver of the decision-making process? It is our informed view that the decision-making is on a similar par with the role design process discussed last week, both are building blocks for the organisational design.

When exploring organisations and management another observation by Dr Elliott Jaques comes to mind, "Management is in the same state today that the natural sciences were in during the 17th century." He went on to explain that during the early Renaissance, alchemy was still considered credible; bloodletting was a well-accepted cure; and barbers performed most surgical operations. He went on to say, " Today, there is not one single, well-established concept in the field of management on which you can build a testable theory."(Kleiner A, 2001)[ii]

This newsletter sets out some of the issues around decision-making to consider when designing a new way of working and managing an organisation that can cope with all forms of change as its day-to-day business, whether the change is reactive, proactive, or predictive.

Decision-making

We solve problems and make decisions every day, all day: at home, at work, and at play. Some problems and decisions are very challenging, and require a lot of thought, emotion, and research. Others are repetitive and matter of fact that are given little if any thought by the decision-maker.

Behavioural scientists have long studied how human beings make decisions. There are several well-known decision traps or fallacies that we all fall into when making decisions. Exploring these in detail is beyond the scope of this article and are covered comprehensively in a future newsletter. Basically, they are distortions and biases — a whole series of mental flaws — that sabotage our reasoning.

Management decisions

Every organisation needs to make decisions at one point or other as part of the business process, and as such, decision-making is still an integral part of modern management, albeit increasingly with the assistance of AI and comprehensive IT support. Essentially, rational, or sound decision making is taken as a primary function of management. Every manager makes hundreds of decisions subconsciously or consciously, making it probably the key component in the role of a manager. The opportunities for non-manager roles to make decisions is extremely constrained and, in some instances, non-existent; hence the time-consuming process of escalation of decision-making to the next level is often the norm in organisations.

The processes of decision-making tend to be complex and involve professionals of different genre. Except in the case of minor day-to-day business decisions, small organisations tend to involve all levels of managers whereas large and complex organisations often rely on a team of specially trained professionals who make all sorts of decisions for the benefit of the organisation. However, such a team cannot come out with final decisions alone because the decision-making process is a cumulative and consultative process. Discussions and consultations are two main tools that support and eventually bring out decisions.

Business decisions

The process of discussion and consultation is taking place across the whole organisation at all levels simultaneously. As decisions are seldom discreet and usually impact on the whole system, there is also an ongoing process of sequential transfer of information and decision-making before coming to the final decision. During such processes the tedious looping (iteration) that often takes place is further cause of slow and ‘politically motivated’ responses. When making a business decision it is not possible to discount the impact of the individuals’ own decision-making influences on that decision, conscious and unconscious; these also create group influences.

The politically motivated responses tend to be caused by the functional silos protecting their power and the management ensuring their hierarchical status is acknowledged in the process.

Decision rights

Whilst anybody can make a decision, it has no relevancy unless it has a force of authority within the organisation and the context within which the decision is made. The authority to make decisions is not something that a person is able to just decide for themselves. Organisations have their own methods for making it clear who has the authority and associated rights, power, or obligation to make decisions and the duty to answer for their success or failure. This makes sense because if this authority is not clear it is difficult to act as any disagreements may make decisions impossible.

Whilst there is no single answer to the spread of decision rights in an organisation, the rule of thumb is based on a mixture of complexity, impact associated to risk, and trust. The more complex and riskier, the higher the level of decision-making. Where there is trust, delegated authority to a lower level is often the case.

Examples of the types of decision authority are:

Accountability – is a duty to answer for the success or failure of a decision. In most organisations it can be agreed that the CEO is accountable overall for every decision the organisation makes.

Responsibility – is the duty to make a decision. It is possible for a person to be both accountable and responsible, although these may be separated. For example, a manager may be accountable for a decision and a member of the team responsible for making the decision.

Delegation – this is where the decision-making authority is granted to another person and yet the person delegating this cannot delegate their accountability for any decision the delegated person makes.

Approval process – it may be necessary for decisions to be approved by multiple people and/or groups in line with a pre-defined approval process. This is a common form of internal control where duties are segregated. For example, a manager may approve a travel ticket for a service engineer to go to a customer overseas and then must submit the approval to the travel department and accounts for final approval.

Consensus – where a decision requires the consensus of a group, they usually follow predefined processes, of which there are many variations.

Consent - agreement on a decision is reached when no one voices a reasoned objection. Failure to raise an objection allows the decision to move forward with any necessary support for implementation implied.

Automated decisions – this is an area that is increasing as AI and other forms of automation become more popular. It is important to note that the automated decisions are based on the authority of the managers who operate the systems making the decisions. This means that those managers are accountable and responsible for the decisions made by systems under their control. It is not the IT people who support the system, which is a common mistake to make when looking for accountability.

The ‘perceived’ hierarchy of decision-making

If we take just one common decision - what type of new product to introduce - and see just how many levels within an organisation are typically involved, the process can be very complex and involve not only different perspectives but also different organisational functions, expertise, and levels.

For example, the decision to be made is whether to introduce a new comprehensive high-end entertainment system at a high price or a series of cheaper individual free-standing components that collectively equal the expensive system and yet can also be sold individually in cheaper customer segments. This is typically a senior management decision.

The manufacturing facility manager has to decide what to manufacture in-house and what to buy-in. The financial manager has to decide whether to invest in new plant or lease. Whilst the marketing manager is confronted with different pricing and segment options to decide upon, the HR manager will have to decide on the skill sets, compensation schemes and work conditions required for such a new endeavour. In some organisations the HR manager cannot decide and can only advise other managers who then decide in these matters in this situation.

All these managers will be advised by a mixture of personal experience, external market trends and expert advice from in-house staff or external specialists to name a few.

Decisions are normally taken based on past experiences and present circumstances for a future course of action. However, the use of AI and the rapid changes in the business environment is encouraging decision-makers to be more aware of using prediction methodologies whenever possible, such as ‘hard predictions’ and ‘soft predictions.’ Hard predictions are things that will happen, such as a new law will be introduced on a fixed date, which enables the organisation to prepare for its impact. Whereas soft predictions are things that may happen because of the new law and become opportunities to take the initiative and create a new product or service before others realise the need, for example. At times, a soft prediction will initiate a decision that embodies a hard prediction that cascades to other decisions.

Once each level has made their preferred decision choices, it is not uncommon for the whole package of decisions to be referred to senior management (executive or board level) for final agreement and strategic sign-off.

The process of decision

Whilst decision-making is essentially an individual process, it must be remembered that it is a process that occurs in an organisational context. The decision-maker is the central focal part of a role-set of others (see Figure 2) that includes supervisors, peers and colleagues, subordinates, other organisational components, which include other departments and their managers.

Figure 2: A role set example

Image: Butterfield (2002)

The decision-maker is also influenced by many aspects of the environment, internal and external. These internal aspects can include issues around power, politics, and ongoing hot or cold conflicts. The external includes competitors, suppliers, customers as well as general environmental factors such as technology and the economy.

The blame game

Very often decision-making is seen as a binary world of success or failure. Leaders enjoy celebrating their successes and as we can see from the Covid-19 pandemic situation, they also seek to lay blame for their failure, typically on others. This blame game tactic is synonymous to business and political leaders. Beijing and Washington - Xi Jinping and Biden; the EU and UK (Brexit) – Ursula von der Leyen and Liz Truss, are just a couple of current examples of leaders finding blame in others.

In the business world this trading-off blame onto others is “normal business” for many people. For example, John is going to meet his business unit executive vice-president to discuss a major product launch. He knows that there are quality problems, and he needs to delay the launch even though marketing has spent a fortune on preparing for the launch. John spent the whole morning with his team to find who they could blame for the situation, even though it was their responsibility. Sound familiar?

This wasting time pointing fingers, rather than looking for solutions, is a common occurrence and far from constructive. It is a built-in defence mechanism caused by the fear that making a mistake or a wrong decision is a death wish as far as careers go. This means that managers will protect their turf at all costs and find a way of passing fault onto other business units or colleagues involved in the overall process whenever possible.

The implications of playing the blame game are wide and detrimental in more ways than the players of such games realise. Such as: detrimental impact on performance, scapegoating, discrimination, lack of trust internally and externally, reduced innovation, ensuring that real talent will not want to work for such an organisation, dissatisfied customers, and much more.

The current approach to resolving such situations tends to be establishing clear responsibilities, which has not stopped the games being played as the players just become more skilful through a range of tactics, many of which are hidden from sight. These include, exclusion of weaker players, hidden finger pointing and bad mouthing in private, and developing a negative fault-finding approach that holds people back. Also, there is a high likelihood of passive-aggressive behaviours with a lack of follow through on any “commitments” made.

Those managers who are well versed in this art of blame have another tactic – involving others in the decision-making process so that there is a wider circle of people to blame when it goes wrong. This can also enlarge the decision-making group to unworkable proportions.

Alternative approaches

It can be no surprise that bureaucratic multi-level organisations are breeding grounds for such behaviour and that alternatives are being sought to cope with today’s increasingly complex and fast-moving business world.

Some of the organisations that we have examined use the Holacracy or Sociocracy[iii] models of organisation and their complex decision-making processes as an alternative to the ‘traditional’ bureaucracy. This decision-making approach is based on a hierarchical form of circles and multi-roles that enable a more consultative approach to decision-making and management. The irony is that we have found them to often have a slower and more bureaucratic order of decision-making than the bureaucratic organisation they set out to replace. They replace one form of decision bureaucracy with another driven by meetings and decision documentation.

Organisations such as the health care organisation Buurtzorg are very different. They have used a network approach based on the collaboration of teams with virtually no prescriptive methods of decision-making or hierarchy. It is a very successful role-focussed approach with the minimal of support structure that enables almost instant local reaction to changes in the environment through individual decision-making and the promulgation of best practice across the teams, daily. It has demonstrated its suitability for its industry and is spreading world-wide with international government encouragement and support. There are many more examples of successful organisations breaking away from the traditional bureaucratic model and most use this collaborative network approach, or similar, in their business.

Summary

Today we started with the premise that decision-making is one of the key foundations for the design and management of organisations. We have identified and discussed some of the organisational issues surrounding the decision-making process. In doing so, we mentioned the extensive work of Dr Elliott Jaques, which helps us to understand the importance of not just a role, but also the need for the appropriate cognitive ability necessary for that role to be implemented successfully. It also reinforced the tight fit between accountability for getting the job done and authority over the resources needed to do so, which includes decision-making. We ended this first part with the games of blame that are played out daily across the business and political landscapes. As a link to the next week’s newsletter, we mentioned Buurtzog as one of many organisations that have managed to build their business around distributed decision-making and authority.

Next week we will explore ways of implementing decision-making in non-hierarchical organisations. In doing so we will look at the things that need to be considered when making decisions and how the use of Principles and Guidelines, together with limited processes to support the distribution of decision-making to the most appropriate level and position in an organisation.

[i] Jaques E., (1998). Requisite organization : a total system for effective managerial organization and managerial leadership for the 21st century (Rev. 2nd ed.). Arlington, VA: Cason Hall. pp. 2, 33–42. ISBN 978-1886436039. OCLC 36162684.

[ii] Kleiner A, (2001) “Elliott Jaques Levels With You”, ORGANIZATIONS & PEOPLE January 1, 2001 / First Quarter 2001 / Issue 22 (originally published by Booz & Company)

[iii] Sociocracy is the foundation upon which Holacracy was designed and developed. Holacracy is a commercially based business model used by companies such as Zappos.

[iv] Korhonen, Janne J.; Hiekkanen, Kari; and Heiskala, Mikko, "Map to Service-Oriented Business and IT: A Stratified Approach" (2010).

Dave, Thanks for the head-up re Farnham Street. I will explore what they have to say.